- Home

- Jackie Parker

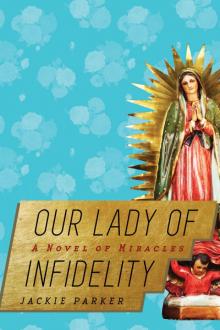

Our Lady of Infidelity

Our Lady of Infidelity Read online

Also by Jackie Parker

Love Letters to My Fans

Copyright © 2014 by Jackie Parker

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First Edition

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Arcade Publishing® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Parker, Jackie.

Our Lady of Infidelity : a novel of miracles / Jackie Parker.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-62872-430-1 (hardback)

1. Miracles—Fiction. 2. Spiritual life—Fiction. 3. California—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3616.A745225O97 2014

813’.6—dc23 2014009096

Cover design by Rain Saukus

Cover photo: Thinkstock

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62872-474-5

Printed in the United States of America

PROLOGUE

There is a form of love so beautiful we can hardly stand to be in its presence. Given where we live and what we are, it is simply beyond us. We know that now. But there was a time here in Infidelity, an unbearably hot end of August into September, when we got to taste it. When it tried us out and found us wanting.

It came to us through a child, Luz Reyes, a name that few of us had pronounced, though she lived (along with her mother Josefina Guerra-Reyes) nearly six years at the margins of our lives. First, a few miles up the freeway in a converted garage behind the auto shop belonging to Bryant Platz. And then, later, right among us in one of the stucco bungalows in the hill district, a small brown rise just up from where the church used to be.

Some claim it was not Luz at all who was responsible for what arrived in Infidelity that August the fifteenth. That it was far more complicated than her so-called gift. Right from the start the skeptics among us were casting about for blame, trying to figure who was behind that car wash vision that had us all confounded. They had their pick of candidates.

Walt Adair is usually named first because it was his window—his car wash. Though Walt had mixed feelings about the whole thing right from the start.

Some blame Josefina for not dragging her daughter off that sidewalk right away and giving her a good hard slap. Others say the beauteous Zoe Luedke was the cause. Here one day, gone the next, golden-eyed, graceful, and shy. Hers were the hands that put in the window. Strange hands too, long-fingered, maimed. An accident, some say of that chopped-off finger. That husband, the rumormongers whisper.

In the end, most people settle on Father Bill. Never mind that we were ripe for it—what he stirred in us, the hunger for something we had not known was missing. The promise we could not fulfill without him. Though in the blame department we are none of us exempt, because all of us took and most of us got and no one considered what it might cost Luz.

Any way you view it, something happened to a child here and we let it.

The day it started was hot. Summer in the High Desert no one’s expecting snow, but this particular August the fifteenth dawned so hot even the Joshua trees woke confused, their gray wooly branches pointing down to the earth instead of up to the impossibly blue and cloudless desert sky.

At least that was the report from the campgrounds ten miles east of here. Strange reports up and down the freeway in Infidelity that day. The dependable griddle at the Infidelity Diner burned everything that touched it—buttermilk pancakes to tuna melts. Tourists in the sliding-door view rooms of the Infidelity Motel awoke to a racket of sand against glass that completely obscured the trio of Joshua trees and the snow-capped San Jacinto peaks they’d paid extra to see.

One hundred and three on the Joshua Freeway and not quite eight. The sun, a molten globe, burned fierce and white. Drivers heading east would speak of the glare. How they had been nearly blinded behind their windshields and had to proceed through Infidelity on faith. Up the steep Joshua grade then headlong into the bowl of it. Just swimming that morning, they all said, with unearthly light.

And Luz Reyes, the child who would become for a while the center of all our lives, steps out of her house in the hill district, 9 Mariposa Lane, headed for Our Lady of Guadalupe and eight o’clock Mass but ends up at the car wash—a long mile away.

There she stands on the sidewalk outside Walt Adair’s front office, thick dark braids down her back, her starched yellow dress limp with sweat, new sandals coated with High Desert road dust. Called, she will later claim. Called by what? She is right out there staring when Walt looks up, checking traffic. Walks out to find her all alone.

“What are you doing, honey?”

No reply.

“What are you looking at?”

She turns her squarish head and faces him, eyes rolled skyward like the answer is up there and she is trying to pull it down. Walt is a dad, he knows the look—she is making something up.

“Big wings.”

“Big wings, huh?” He glances into the brilliant empty sky. “What, a hawk?”

“The Quetzal.”

“Never heard of it. Did mother bring you down here?”

She shakes her head.

“Does Father Bill know you’re here?”

No again.

“Who brought you, Luz? Did you walk off again on those fast little feet?”

Still no reply.

Her cheek is hot as a furnace, and there is something about her smell, Walt says later. Like someone has doused her in rosewater. Sun poisoned. He lifts her up and carries her to his office where it is cool, then sits her on the sofa. Luz drinks some water, lets him wash down her face with a wet paper towel. Then he grabs a handful of ice from his fridge case, slides a cube along her palms and wrists, a trick he remembers from his own kids’ fevers. The whole time she’s staring across the room—at that crazy window.

“So Luz, how did you get here?”

“A lady told me.”

“What lady?”

She closes her eyes and begins to speak—the words he can never bring himself to repeat—floored by what comes at him next, some feeling between thankfulness and ordinary love. But bigger. A lot bigger. What the hell? he thinks.

“How ’bout we call your mother.”

Then across the room Luz runs, banging out the door, ice cubes flying behind her. This time when Walt tries to lift her from the sidewalk she fights him off. When he cannot reach Josefina by phone, he tries everyone he knows in the hill district, until old Wren Otto drives to the church and calls out Father Bill in the middle of saying Mass.

By the time they arrive—Father Bill and, a little while later, a dozen or so of his faithful—Luz is kneeling on the sidewalk, tears streaming. Enraptured.

Father Bill kneels next to her, covers the top of her head with his hands and tries talking ordinary sense. He cannot bring her back. A good hour he is at it, his black robe still on from Mass soaked through with sweat and reeking. He had thrown up.

Finally, he shouts, “Stop it, Luz!”

Then Luz starts in with the noises, deep in her throat. A few folks fall to their knees. Some start moaning.

“Oh, God no. Please.”

“Luz, listen to me, now,” Walt says. “No more nonsense. I want you to get up!”

She doesn’t.

The sidewalk is hot enough to scramble egg whites. But Luz will not remember the heat, only that suddenly there were green wings above her, the wings of the Quetzal (already extinct in her country and never, of course, seen in the Mojave), the sweet smell of roses and cedar, and a deep coolness before she ceased to see.

Josefina Reyes will recall nothing unusual about the start of that day save for a leftover blueberry waffle. But within herself, Josefina confesses, she had awakened with a certain unreasonable joy. Though she is only one week out of the hospital with the warnings of her doctors still fresh in her ears, she feels perfect, absolutely restored, exactly as she knew she would feel, impending dialysis and incipient uremia be damned. Filled with her old energy.

Right before Luz leaves the house, Josefina kisses her daughter three times on her broad, stony forehead, reminds her to drink one glass of water per hour, to stay off the hot playground at summer school, and repeats the daily injunction: a half-hour of reading will do more for her future than going to Mass.

“Don’t waste time saying Rosaries for my health, for my body has already cured me. And no little tricks with your Zoe. No campgrounds, no makeup, even if it is her last day.”

Then she brings Luz back through the house to the kitchen and opens the refrigerator to show Luz the syrup she has prepared—one pineapple cored and blended, four ounces of guava paste, a scant cup of sugar.

“See how I slave for your sweet tooth, gordita? Make the refrescas to be cool. Zoe scrapes the ice. Listen! You only pour. Don’t touch the big knife.”

“Ay, Mami, you are hurting my ears. You are so bossy again.”

“Be glad. This way you know I’m not dead.”

So thrilled is Josefina with the return of her strength that she does not accompany Luz to the front door. She has decided, in the ten minutes she has left before driving to work, to sweep Luz’s room and straighten the dog-eared Madonnas of the Centuries that only the most tolerant of nonbelievers would allow her daughter to tape on the walls throughout a four-room house.

As soon as the front door closes behind her, a voice directs Luz to the car wash, urges her a long mile in terrible heat in the wrong direction. Not for a moment does she consider ignoring it, she says later, so kind it is, unfamiliar, yet still, a voice she knows.

Josefina herself, driving at a snail’s pace through light brilliant and granular as snowfall, passes her own daughter unseeing.

And all of us who are used to the sight of Luz Reyes walking to Mass in her starched yellow dress, the thick dark braids down her back, watch her turn right instead of left at the end of Mariposa Lane, stepping onto the shoulder of the freeway. Yet not one of us opens a window or a door that day to ask where she is going. We did not want to interfere, we said later, for it was clear from the purposefulness of her step that Luz knew exactly where she was headed.

August the fifteenth, the day of Our Lady’s Assumption. A coincidence, many of us believed, and perhaps still do, one in a long string of coincidences—or a hoax, venal and cruel. Or something far greater. Who among us can say for sure?

CHAPTER 1

The first time they are together is at Father Bill’s table, a Wednesday or a Thursday. No one remembers exactly—a sweltering August night. Father Bill at the head, Josefina seated stiffly to his left, then Luz, head down and hands in her lap so she won’t stare. Across from Luz there is Zoe, the creamy skin, the yellow-brown eyes, and other things Luz is dying to look at—like that hand. Next to Zoe Father Bill put Walt, overdressed in his usual blue oxford, amazed that the woman he has been musing on for days has turned up beside him.

The room is plain, nearly empty of furnishings, the not-quite-steady table with a frayed white cloth, six mismatched hard-back chairs and no cushions, and the tall west-facing windows through which the light of High Desert sunset now pours. If only they would look out, the San Jacinto Mountains are turning silky pink just beyond them, but instead they are admiring his food.

Father Bill will say he had no idea what would come of this night. That it is simple gratitude that made him ask Zoe to join him for a meal. What else does he have to give to a stranger (a Samaritan, truly), but his passion for food, his talent to feed? Now he thanks them all for coming and then starts the blessings, first them, then the focaccia, the rosemary chicken, the eggplant parmesan, the broccoli with lemon zest, the frozen cannolis, and two flavors of ice cream that Luz will scoop out for dessert. He thanks his late mother in heaven for the recipes, thanks the fourth ward of the city of Newark, New Jersey, where he was raised, Italians in row houses, the air thick with garlic and sauce. Thanks his uncle Gerard whose three-meat gravy he was wise enough not to make in such heat, and the province of Calabria, his ancestral home, where even now the men who walk the high cobbled streets have his thick black hair, his narrow-set gray eyes, and munificent, unbalanced tables.

“We are here, Lord, not just to nourish our bodies but to nourish one another.”

And then he pours the wine. They follow him as he lifts his glass.

“To Zoe Luedke, hero of the day. The one who rescued me from sunstroke.”

Everyone must drink. Luz takes a sip of her orange juice, careful not to dribble, and crunches the ice in her teeth. Josefina thinks of dousing Father Bill with the chilled Chardonnay, which she knows she should not, in her condition, swallow but will just to spite him because she has heard too much already about this Sewey. And now here she is seated across from her daughter—what does he know of her—a woman who picks up men in wild shirts on the freeway: a woman who from unearned beauty is no doubt used to too much attention. Look how she flaunts that face—no makeup, such easy smiles. But too tall, too pale, the fine hair that does not hold its color, and the unpronounceable name. Sewey—and in the same breath as hero. He is crazy. He is a forty-five-year-old teenager, already half-mad with love.

“And these are my girls. Josefina and Luz Reyes.” He says their names properly at least.

“Hose-a-fina and Loose,” repeats Zoe, as if she has never heard Spanish.

“Pretty good,” says Father Bill, turning to them, “don’t you agree?”

Josefina barely nods. She has that look he hates. She could shut down like a tainted clam and spoil the whole meal. Luz feasts her eyes on the stranger, gold in her hair, gold in the brown of her wide, shining eyes. Zoe, she says to herself. A gold ocean appears in Luz’s mind.

At last now they can eat.

They pass the platters, which are heavy, the same blue misplaced windmill design as the chipped plates that are filling up fast. Luz gets two chicken legs, a large square of eggplant, even the broccoli. She digs right in. She never waits. Josefina watches as if her daughter’s eating is a sport and she’s the coach, Walt thinks, amused, Keep going! Good job, mamita! It is always like this. The child eats; the mother watches. Luz has arrived on first base. Josefina can relax.

Walt helps Zoe to chicken. He is so nervous beside her (the long bare arms, that lovely white neck, and the vulnerable collar bones—his undoing in a woman—such creamy skin), he must focus to hold the heaping platter steady while she reaches, twice, once for a breast, then for a thigh. “There’s so much!” she says. “And I’m starved.” A sudden rush of joy courses through Walt; her voice affects him like music—so many risings and fallings in so few words. What will he do if she says more than three at a time? “That’s good!” booms Walt, “This is the place to be hungry.” When she offers to serve him the steaming eggplant, it nearly slides from the spoon onto his perfect blue shirt. They laugh, apologize to each other. On one side of the table the tension breaks.

“So what’s the word on your car?” Father Bill asks. Zoe has driven to the rectory in Platz’s garage loaner, a hulking Dodge Dart.

Zoe swallows her chicken. It is wonderful—so tender (he bastes it every quarter hour in b

rown butter). “A cracked radiator. Unfixable. Platz says it could take a week before he finds a replacement. A ’78 Nova, it’s a hard thing to find.”

A week, thinks Walt, perhaps even longer.

“What a pity. And mine was only minor, all that steam and just a hose,” Father Bill says.

Josefina nudges Luz, who smiles.

“Did someone say something funny?” asks Father Bill.

“No-va,” says Luz and gives Zoe the force of her penetrating eyes and a mouth full of eggplant. Josefina wipes the mouth. Luz squirms and continues, “You know Spanish? No va. Does not go.”

Zoe slaps her forehead. “Now they tell me!” The minute she does it she realizes she has made a mistake and quickly puts the hand in her lap. Josefina feels sick to her stomach. She turns her head to Father Bill; her thick black hair conceals half her face, her features already obscured by the swelling that makes her look like she has just been roused from a bad sleep. She whispers to Father Bill in Spanish. Father Bill whispers back in kind.

Now they have seen it, Zoe should tell the story of her missing fingertip, which always puts people at ease, but to tell it she will have to speak of her husband and to strangers. She returns to her food, hoping nothing more will be made of the finger, but the table has gone silent.

“Something wrong?” Walt asks.

They are waiting for her to explain.

“An accident at my shop. The most common injury there is for woodworkers.” Zoe holds up her hand—missing fingertip and all—for them to see again.

“Does it hurt?” asks Luz.

“Not at all.”

Josefina puts her own intact hand on Luz’s arm, “Co-may, mamita.”

It had happened three years before after an impromptu picnic. The first time she and Michael had made love. Cold Spring in autumn. Golden oaks and scarlet maples spilling their colors into the blue of Long Lake, air tinged with frost. “I knew it would be like this,” Michael says, enfolding Zoe in a blanket. “Like what?” she whispered. “Like home.” Lovemaking to scramble the senses. Wine at lunch, forbidden in the wood trade. She’d sliced her finger clean through at the joint on a Grizzly Saw. When he raced to her, the table saw running, eight feet of walnut spun out at the kickback. Michael tore off his shirt, wrapped the finger, retrieved the tip, drove to the hospital berating himself. “Don’t fall for me. I’m bad news.” Too late, Zoe thought. And then said so. Both of them laughing, giddy with shock and relief. And so it began. Hermit-girl and the man she had loved since high school. After years of aloneness she was finally home.

Our Lady of Infidelity

Our Lady of Infidelity