- Home

- Jackie Parker

Our Lady of Infidelity Page 2

Our Lady of Infidelity Read online

Page 2

“Zoe is a carpenter, Luz. She has a red toolbox,” Father Bill explains.

“A cabinetmaker, kitchen cabinets mostly. My shop is very far away. In a place called Cold Spring.”

“You know how to use tools?” Luz asks.

“I do.”

“Comay,” Josefina insists.

“No, because maybe she can give Walt his window!”

“That is not your business. How many times must I say you do not worry for the world!”

“Let’s not start on my window. Not tonight, please!” Walt laughs. His smile is genial. The sun creases are white around his deep-set blue eyes, something worn and expectant about his face. At forty-five, his skin has freckled (too many hours on the tennis court—in the old life). Zoe softens and forgives him for the way he kept her the night she drove the grubby Dart through his car wash. Walt standing in the exit lane wanting to talk, she inside the car in tears, wanting only to leave.

“That window is just waiting for someone to trip over,” Father Bill says, picking up his wine glass.

“No one’s fallen yet, Father. It’s still in one piece.”

“You’ve been lucky.”

“It’s behind the couch now.”

“Is that progress?”

Father Bill laughs at his own little joke and finishes his wine. Even Josefina seems amused. Walt deserves this, he knows. His window, again. These days everything he does takes him long to decide. The design of his wash, one year to come up with, the window he has bought but can’t figure where to put, the coupon books he has for months debated if he should offer, these are decisions that do not make themselves. So they laugh at him, the people of Infidelity—who have not much to laugh at, truth be told. Walt is used to it. On the days he’s feeling thin-skinned he avoids the diner crowd, or if he can’t he ignores their remarks, does not take the bait when it’s been tossed. He knows his window was a mistake. He should have returned it right away. A single-glazed horizontal slider bought on sale at Home Depot, all wrong for this hot climate. What was he thinking? He was thinking it would give him a view.

“Well,” says Zoe, “I’ve installed windows.”

“I’ll keep it in mind. But I’m sure you don’t want to work on your vacation. You’re at the campgrounds?”

“Yep. Still there.”

“And you’re a crag rat—a climber?”

She could tell Walt she had come for the sights, for the desert, for the climbing at the campgrounds, which is what she told her customers in Cold Spring, even the ones who knew better. It is fifteen dollars a week at the Joshua Tree Campgrounds and somewhere in the vicinity her husband may be waiting, not for her, but still he may be near.

“Not yet,” she says and hopes they’re too polite to question her further. “What size is the window?”

“Four by six.”

“It would only take a day to install.”

“Thanks. I’ll think about it.”

They go back to eating in silence, Zoe relieved. She has managed to deflect the conversation away from her life and onto Walt’s window, which has brought a little levity to the table at least, and who knows—maybe a job. There is no radiator on order at the Infidelity Garage because Zoe is strapped. Four breakdowns of the Nova on her crazy trip west and bills piling up in the Cold Spring post office. Old house. New shop. Expensive equipment. They had taken on too much. Way too fast.

Father Bill urges a little more food on his guests. Who can refuse such tastes even if the body must be stretched to receive them? And besides, it is cooler, have they noticed? They have all ceased to sweat. He opens the second wine with a flourish and a pop. From under Father Bill’s wide-flung casements, the cool desert air wafts in like a reasonable neighbor come over to offer relief.

Luz takes a drink of orange juice, looks straight across at Zoe, then pushes back her chair and stands up.

“What’s wrong, mamita?” Josefina asks as Luz begins to walk. “Come back. Sit down and finish.” Luz does not obey, walking to Zoe, bending close now to whisper, so softly that Zoe must ask her to say it again when she’s through. After Luz has whispered for the second time in Zoe’s shiny ear, she stays with her hand on that strong, bare white arm.

“You heard it?”

“Yes.”

Luz can return to her seat.

At the place where Luz touched her, Zoe feels something rise under her skin and spawn out through her blood, like the bubbles of a thousand silver fish rushing to the surface of a lake. Now she feels it in her shoulder then straight down her spine. Luz is already back to her chair, but Zoe is being run through with lightness, she sees it, how can she? A silver sensation like a stalled AC current is stuck at the base of her neck. She is tipping, falling backward. It is Walt who grabs her chair just in time.

Now Zoe has risen to her feet, quite surprised to find herself upright. Immediately Walt stands up too—“Shall we clear?”—and reaches across for her plate.

Josefina has gone pale. She takes Luz’s face in her hands. “Did you say something crazy? What did you tell that woman that no one else could hear?”

“Josefina!” Father Bill says sharply and asks Zoe and Walt to sit down.

“It must be the wine,” Zoe says, sorry she has caused such a fuss when already the sensation has passed.

“Or the heat,” Walt adds.

Once she is seated, Zoe feels downright foolish.

“Your little girl asked me again to help Walt with his window.”

“Because they always laugh at him,” Luz says, training those dark eyes at her mother.

“Oh, honey,” says Walt.

Now Josefina looks contrite. “Come here, mamita.” She pulls Luz onto her lap.

“There, you see? It was harmless.” Father Bill puts his hand on the top of Luz’s head and holds it long enough for a blessing. “How about it, Walt, shall we clear?”

Luz burrows into her mother’s soft breast like an infant. Josefina kisses her forehead, her cheeks; she is kissing Luz’s hands. It is too much for Zoe, who averts her eyes.

As the men leave the dining room with the platters and plates, Zoe looks out the window at the darkening mountain, breathes deeply, inhaling the cool rush of sweet night air. It is her own fault she nearly passed out, Zoe thinks. It is Michael’s. Or it is the breakdown-plagued trip west. Maybe even the climate, the heat, the dry air. Her dizzy spell had nothing to do with the touch of a child whose mother adores her, who is right now allowing those kisses.

“You like ice cream?” Josefina asks in heavily accented English.

“I do,” Zoe says.

“Prepare to wait for it, then.” And she laughs, a big careless laugh that is startling. “Because with my daughter serving we will have to be extremely patient.”

It is the first time all evening that Josefina has spoken directly to Zoe.

“I have been told I am patient to a fault,” Zoe says.

“To a fault? What does it mean?”

“I can be too patient.”

“No one can be too patient.”

Ah, yes, yes they can. Zoe waited two weeks after Michael left before accepting he had actually gone. She stands at her workbench for hours, days, wrecking her schedule while she waits for the grain of the wood to reveal itself before she will make the first cut. This evening, she will be happy to wait a few minutes for a child to serve ice cream.

Josefina murmurs to Luz, runs her hands down her daughter’s thick braid, then leans forward, puts her elbow on the table, and rests her head in her hand. After a few seconds she closes her eyes.

Zoe listens to the men’s voices in the kitchen, the clattering of plates and cutlery. A few months ago it would be Michael and Zoe in their kitchen cleaning up, cabinets half-stripped, flooring ripped up, guests for dinner anyway. Now the Cold Spring house bought with such hope is deserted, the unfinished rooms, their shop in the back, empty of life. The slate-gray Hudson moves along without them in the unseen distance.

Out

side it is growing dark, the High Desert night sky taking on a blackness whose depth Zoe does not recognize. So many stars it makes her giddy. For three nights she has lost herself watching the desert sky expand under darkness. At night it seems wider even than in the piercing blue day, when it is already so vast she has to stop looking or she’s afraid she’ll dissolve. How different the sky is in this part of the world, Zoe thinks, as if up to now she has been given only a glimpse of all that is actually there. In a little while she will be unroofed and under it again: the noisy Sheep Meadow campsite, her collapsing two-person tent.

When Walt returns, he does not seem surprised to find Josefina asleep at the table and carefully sets the dessert bowls, a glass of water, and the ice cream scoop before Luz, who looks up and smiles but remains on the lap of her mother. When he returns to his seat, he bends quite close to Zoe, so close she can smell him, clean, the undertone of alcohol on his breath, musk, a familiar cologne. A wash of surprised desire runs through her.

“How are you doing?” Walt asks in a hushed voice, so as not to disturb Josefina.

“Much better, thanks.”

“I’d like to explain about the other night.”

“Oh,” says Zoe. “Really, it’s not necessary.”

Luz climbs carefully off of her sleeping mother’s lap, takes her seat, and watches Zoe reach for her wine glass with that hand. It is a big hand and white. The skin over the missing fingertip perfectly smooth.

From the outside Walt’s car wash had looked a little sad, a white forlorn barn dropped down in the desert. A hundred yards off sat Walt in his office (or so she had thought), a small stucco box built so close to the freeway you could walk out the door, follow the path to the sidewalk, and be hit by the wind and the heat from the onrushing cars.

“Don’t you think all the lights in the wash are so beautiful?” Luz asks in a whisper.

“I guess so. Yes. They are.” Inside the wash there were hundreds of delicate overhead lights that began flashing as soon as she’d entered, then the water rained down in a slow, dreamy whoosh. The lights flickered, grew faint. For a moment it was quiet and dark. Zoe was overcome with a great feeling of peace. The cycle resumed, water pounding, lights brighter, and by the time it was over Zoe could not stop her tears.

“Lots of people break down at my car wash like you did. The lucky ones.”

“Lucky ones?” Zoe laughs nervously.

Walt smiles. She thinks he’s joking. He does not have the words to convince her he is not. He really is handsome, Zoe thinks, even-featured, too even, too well put together, like one of her well-heeled clients. Now the ice cream is here. Father Bill with his green parrot shirt and his self-effacing warmth, wedging two gallons under his chin. When he puts them before Luz, she takes off the tops, dips the scooper into the water glass then into the first container, making a perfect pink round of peppermint ice cream in very slow motion, before easing it into its bowl. Now the water glass to rinse, now the green ice cream: pistachio and soft enough to scoop. Pistachio and peppermint, her favorites that Father Bill always gets for her. She holds up the first yellow bowl like a trophy. “For Zoe,” Luz says. Father Bill hands Zoe the bowl. Josefina opens her eyes and sits back, forcing herself awake.

“I think our guest should start or she’ll soon be drinking soup,” says Father Bill. “By all means,” says Walt. “Okay, here goes,” Zoe says as she puts her teaspoon into the pink mound and begins.

When at last the meal is over, the cannoli dish empty, the ice cream a memory, just before they all rise and go out into the cool starry night, Father Bill looks from one to the other appraisingly. Then he smiles.

“What are we waiting for?” asks Luz, breaking the silence. Even Josefina laughs. Then the thanks begin and the offers to clean up; Father Bill, refusing, walks his guests to the door. “We did very well, don’t you think?” he asks as if he is not quite sure. “I think we should do this again.”

“I’ll have you for dinner at the campgrounds,” Zoe jokes.

Luz looks from Father Bill to her mother. Walt turns around on the step. “We are going to the campgrounds?” Luz asks.

“Come, mamita,” says Josefina, taking Luz’s hand and rushing into the dark with barely a whispered goodnight.

After Zoe and Walt say good-bye, walking together to their cars, even after all three of the cars are gone from his parking lot, Father Bill remains on the steps of the rectory, following the lights as they take their separate routes through the dark. How unlucky that the evening has ended with a mention of the campgrounds. Now Josefina won’t sleep for worrying.

Tonight she has driven the three short blocks from her blue house to his church, a fine walk but she will not walk in the dark. He has only to look at her face to see that she is having a bad time. She never speaks of it anymore. It is a given. All her symptoms, some physical, some psychological. What is the difference? They persist. He does not go inside until he has followed the lights of Josefina’s car up the hill and into the driveway of her house, which he can just about see from the blistered steps of his church.

Then, ignoring the mess in the kitchen, he walks around to his office, opens the screen door, goes to his desk and sits down to begin the night’s calls. He calls two priests in the greater Los Angeles diocese in the wealthiest parishes. A mercy call, he explains, on behalf of a parishioner without family or funds who may soon be unable to work, worse, might require an organ donation. Both calls evoke silence, offense. He has overstepped the bounds of charity, it seems. Since when does charity have bounds? he wonders. One of the priests asks the parishioner’s name. “I’d like to pray for her. Or is it a him?” A delicate matter, Father Bill explains. He cannot give out the name. The calls end badly, with hollow promises.

When he returns to the wreckage of his kitchen, the great heap of dishes piled in his sink cheers him, and he is able to let go the heaviness in his chest. He feels a deep satisfaction about the evening, as if all he could ask of it has been given. Now he stands at his sink below the dismal brown cabinets Zoe Luedke, a maker of cabinets so it turns out, would have dismantled and replaced in less than a day. He looks down at his dishes, looks further, and realizes he cannot see his feet. His belly has grown quite impressive. No wonder Josefina reaches under his shirt and whispers in Spanish, “We have made a miracle, William. You look six months gone.” Her touch, he thinks, and wonders if perhaps he will go to her later, though he promised himself he would not. Lately her skin feels different—papery, too dry. She is not drinking water.

He turns on the hot water and pours a liberal quantity of blue dish liquid into the sink, watching the bubbles, then takes up the sponge. Or could it be the detergents that are making Josefina’s fingers feel like sandpaper? Does she remember to wear gloves? A woman from a family in which no girl made a bed or washed a dish. Now Josefina is a housekeeper with sandpaper hands. Who would have believed it? And he sighs.

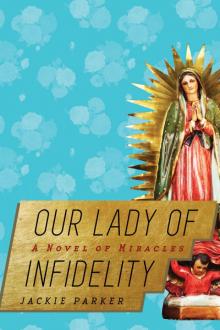

He should be grateful. She takes her medicine. Follows the diet. She works. She sleeps. She is mostly free from fear. And their life together is in many ways beautiful. He has long ago gotten over the guilt of their relation. Now, thanks to a parishioner’s bequest, he has been able to give her a house, for a little while at least, until his bishop insists that he sell it. She pays four hundred dollars a month, one-third her salary, but that is more than sufficient. The neighbors do not comment on his visits to the little blue hill district house. Their own houses are dark when he leaves her deep in the night. If they notice, they don’t suspect why he is there, or so he likes to tell himself. His parish is insignificant. He has failed to attract many believers to Our Lady of Guadalupe (he knows they call it Our Lady of Infidelity behind his back), knows that he asks too much of those who stay. In his state a small failing parish, perhaps it is just as well. He will soon be gone.

Since his escape from the country of death, he has lost his ambition. He is slow in his brain and his blood. So at forty-five he understands better his few parishioners, whose a

verage age is nearly eighty, and he understands Josefina when she says she is thirty-two plus one hundred. It is because of El Salvador, where you live several lifetimes in a month, if you are lucky, and if you survive, as they did, and she barely, a life lived in safety seems like a dream. He had left a promising career in the Newark parishes, drawn by the call of liberation theology. A rising star in the church, he had given it up after he read the reports, a whole town massacred by its own soldiers, Mozote. Every child, every adult save one. And those who told of it, even in the press of his country, were not believed. “You do not want to get into that mess,” his bishop had warned. “There is no profit in it. You can do more here.” He could not remain. He was entirely unprepared for El Salvador. Even in the cities they were killing priests, their archbishop, professors, judges, journalists, imprisoned, disappeared. What they could do to a body—Dr. Raphael Reyes, the charismatic professor of biology—his friend.

To their own bodies, his, Josefina’s, though nearly eight years have passed, it is still El Salvador. You cannot know so many people who have died and not died in their beds but been killed, and not killed but slaughtered, their corpses dispersed like refuse in the green coffee fields, in the black sands, on the highway, the alleys, impaled on the gates. At the university. You cannot know deaths like that so intimately and be young. The whole sense of hope bleeds out of you when you have lived as they have in El Salvador, him for three scant years. Her country, her family, her losses, too large to count.

And there it is again after such a fine night, El Salvador. A night that arrived with a taste of pure happiness. Even in this moment when his body pretends to know nothing of what he has lived, when his body is light and delicious, despite its new weight, happy to have fed and eaten, satisfied with his little dinner and his guests. How can he know a whole day’s joy when so many dead live within him, his friend—more, his brother, Dr. Raphael Reyes, the husband of Josefina, the father Luz has never seen.

Our Lady of Infidelity

Our Lady of Infidelity